RESPUESTAS,... A LO KE HAN MANDADO,....¡¡ :

- HOLA,.... FALTABA,...ESTOS TRABAJOS-ARCHIVOS---¡¡¡- Se incluyen resultados de sobre el multicapitalismo mancomunado mundialmentelukyrh blogspot re

volución de la humanidad. ¿Quieres obtener resultados solo de SOBRE EL MULTICAPITALISMO ANCOMUNADO MUNDIALMENTE/LUKYRH.BLOGSPOT.COM-REVOLUCION DE LA HUMANIDAD? REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD: DOS CONCEPTOS SOBRE ...

1/8/2021 · 15/7/2020 · revoluciÓn de la humanidad miércoles, 27 de mayo de 2020. ... 25 de mayo de 2015/ revoluciÓn de la humanidad - blog-lukyrh.com. ... Con un fuerte, potente, movimiento y fuerza organizada, revolucionaria proletaria y popular,...ya se vería que diríamos, decimos, en una hipotética contienda electoral, ...

REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD: EL MULTICAPITALISMO ...

Aplicar una exención del Impuesto sobre la Producción de la Electricidad para las instalaciones renovables de menos de 100 kW. Igualar los tipos impositivos sobre la gasolina y el gasóleo. Reformar el impuesto sobre vehículos de tracción mecánica para tomar en consideración las características contaminantes de los vehículos.

REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD: "" EL MULTICAPITALISMO ...

17/6/2020 · "" EL MULTICAPITALISMO : ... Y SI ME APURAN DESARROLLAR LAS TEORÍAS E IDEAS EXPRESADAS EN EL BLOG REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD=LUKYRH.BLOGSPOT.

COM,...-PERO OS DECIMOS ... fueron editadas, siendo algunas borradores. Este tema está relacionado con el enfoque de dar una teoría más general sobre las tesis de la revolución de la ... REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD ... - lukyrh.blogspot.com

jueves, 4 de junio de 2020 blog revolución de la humanidad lukyrh.blogspot.

com. la nueva sociedad a crear y las movilizaciones resistencia revolucionaria se van generalizando,…hay que pedir disoluciÓn de la otan,…los ejÉrcitos nacionales, locales,…. hay dos posturas o la una o la otra,…resignarse y que nos esclavicen aÚn mÁs,… REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD: NOTA MANDADA A …

TEORÍA COMUNISMO TOTAL E INTEGRAL EXPOSICIÓN GENERAL SOBRE LA REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD: Proyecto e intento de desarrollar la teoría:"El Capiimperialismo, Crítica a la Economía Capitalista-Imperialista". Proyecto empezado desde 1.998 en Málaga, desde esta fecha se viene publicando asuntos sobre la cuestión.

REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD: ¿¿¡¡ Cuba organiza el Congreso ...

REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD JUEVES, 2 DE JULIO DE 2020 SOBRE LA PLUSVALÍA IMPERIALISTA DEL MULTICAPITALISMO LUKY DE MÁLAGA. Lmm. LUNES, 22 DE JUNIO DE 2020 BLOG REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD "Ahora surge la necesidad de un capitalismo consciente": Alexander McCobin. R. ASTARITA, Y TEORÍA SOBRE PLUSVALIA IMPERIALISTA,...DE LUKY DE MÁLAGA,..¡¡...

- Se incluyen resultados de sobre el multicapitalismo mancomunado mundialmentelukyrh blogspot re

volución de la humanidad. ¿Quieres obtener resultados solo de SOBRE EL MULTICAPITALISMO ANCOMUNADO MUNDIALMENTE/LUKYRH.BLOGSPOT.COM-REVOLUCION DE LA HUMANIDAD?

| ||||

| ||||

- HOLA,.... FALTABA,...ESTOS TRABAJOS-ARCHIVOS---¡¡¡- Se incluyen resultados de sobre el multicapitalismo mancomunado mundialmentelukyrh blogspot re

volución de la humanidad. ¿Quieres obtener resultados solo de SOBRE EL MULTICAPITALISMO ANCOMUNADO MUNDIALMENTE/LUKYRH.BLOGSPOT.COM-REVOLUCION DE LA HUMANIDAD? REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD: DOS CONCEPTOS SOBRE ...

1/8/2021 · 15/7/2020 · revoluciÓn de la humanidad miércoles, 27 de mayo de 2020. ... 25 de mayo de 2015/ revoluciÓn de la humanidad - blog-lukyrh.com. ... Con un fuerte, potente, movimiento y fuerza organizada, revolucionaria proletaria y popular,...ya se vería que diríamos, decimos, en una hipotética contienda electoral, ...

REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD: EL MULTICAPITALISMO ...

Aplicar una exención del Impuesto sobre la Producción de la Electricidad para las instalaciones renovables de menos de 100 kW. Igualar los tipos impositivos sobre la gasolina y el gasóleo. Reformar el impuesto sobre vehículos de tracción mecánica para tomar en consideración las características contaminantes de los vehículos.

REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD: "" EL MULTICAPITALISMO ...

17/6/2020 · "" EL MULTICAPITALISMO : ... Y SI ME APURAN DESARROLLAR LAS TEORÍAS E IDEAS EXPRESADAS EN EL BLOG REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD=LUKYRH.BLOGSPOT.

COM,...-PERO OS DECIMOS ... fueron editadas, siendo algunas borradores. Este tema está relacionado con el enfoque de dar una teoría más general sobre las tesis de la revolución de la ... REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD ... - lukyrh.blogspot.com

jueves, 4 de junio de 2020 blog revolución de la humanidad lukyrh.blogspot.

com. la nueva sociedad a crear y las movilizaciones resistencia revolucionaria se van generalizando,…hay que pedir disoluciÓn de la otan,…los ejÉrcitos nacionales, locales,…. hay dos posturas o la una o la otra,…resignarse y que nos esclavicen aÚn mÁs,… REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD: NOTA MANDADA A …

TEORÍA COMUNISMO TOTAL E INTEGRAL EXPOSICIÓN GENERAL SOBRE LA REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD: Proyecto e intento de desarrollar la teoría:"El Capiimperialismo, Crítica a la Economía Capitalista-Imperialista". Proyecto empezado desde 1.998 en Málaga, desde esta fecha se viene publicando asuntos sobre la cuestión.

REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD: ¿¿¡¡ Cuba organiza el Congreso ...

REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD JUEVES, 2 DE JULIO DE 2020 SOBRE LA PLUSVALÍA IMPERIALISTA DEL MULTICAPITALISMO LUKY DE MÁLAGA. Lmm. LUNES, 22 DE JUNIO DE 2020 BLOG REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD "Ahora surge la necesidad de un capitalismo consciente": Alexander McCobin. R. ASTARITA, Y TEORÍA SOBRE PLUSVALIA IMPERIALISTA,...DE LUKY DE MÁLAGA,..¡¡...

- Se incluyen resultados de sobre el multicapitalismo mancomunado mundialmentelukyrh blogspot re

volución de la humanidad. ¿Quieres obtener resultados solo de SOBRE EL MULTICAPITALISMO ANCOMUNADO MUNDIALMENTE/LUKYRH.BLOGSPOT.COM-REVOLUCION DE LA HUMANIDAD?

| 17:08 (hace 5 minutos) |   | ||

| ||||

- HOLA,.... FALTABA,...ESTOS TRABAJOS-ARCHIVOS---¡¡¡- Se incluyen resultados de sobre el multicapitalismo mancomunado mundialmentelukyrh blogspot re

volución de la humanidad. ¿Quieres obtener resultados solo de SOBRE EL MULTICAPITALISMO ANCOMUNADO MUNDIALMENTE/LUKYRH.BLOGSPOT.COM-REVOLUCION DE LA HUMANIDAD? REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD: DOS CONCEPTOS SOBRE ...

1/8/2021 · 15/7/2020 · revoluciÓn de la humanidad miércoles, 27 de mayo de 2020. ... 25 de mayo de 2015/ revoluciÓn de la humanidad - blog-lukyrh.com. ... Con un fuerte, potente, movimiento y fuerza organizada, revolucionaria proletaria y popular,...ya se vería que diríamos, decimos, en una hipotética contienda electoral, ...

REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD: EL MULTICAPITALISMO ...

Aplicar una exención del Impuesto sobre la Producción de la Electricidad para las instalaciones renovables de menos de 100 kW. Igualar los tipos impositivos sobre la gasolina y el gasóleo. Reformar el impuesto sobre vehículos de tracción mecánica para tomar en consideración las características contaminantes de los vehículos.

REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD: "" EL MULTICAPITALISMO ...

17/6/2020 · "" EL MULTICAPITALISMO : ... Y SI ME APURAN DESARROLLAR LAS TEORÍAS E IDEAS EXPRESADAS EN EL BLOG REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD=LUKYRH.BLOGSPOT.

COM,...-PERO OS DECIMOS ... fueron editadas, siendo algunas borradores. Este tema está relacionado con el enfoque de dar una teoría más general sobre las tesis de la revolución de la ... REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD ... - lukyrh.blogspot.com

jueves, 4 de junio de 2020 blog revolución de la humanidad lukyrh.blogspot.

com. la nueva sociedad a crear y las movilizaciones resistencia revolucionaria se van generalizando,…hay que pedir disoluciÓn de la otan,…los ejÉrcitos nacionales, locales,…. hay dos posturas o la una o la otra,…resignarse y que nos esclavicen aÚn mÁs,… REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD: NOTA MANDADA A …

TEORÍA COMUNISMO TOTAL E INTEGRAL EXPOSICIÓN GENERAL SOBRE LA REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD: Proyecto e intento de desarrollar la teoría:"El Capiimperialismo, Crítica a la Economía Capitalista-Imperialista". Proyecto empezado desde 1.998 en Málaga, desde esta fecha se viene publicando asuntos sobre la cuestión.

REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD: ¿¿¡¡ Cuba organiza el Congreso ...

REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD JUEVES, 2 DE JULIO DE 2020 SOBRE LA PLUSVALÍA IMPERIALISTA DEL MULTICAPITALISMO LUKY DE MÁLAGA. Lmm. LUNES, 22 DE JUNIO DE 2020 BLOG REVOLUCIÓN DE LA HUMANIDAD "Ahora surge la necesidad de un capitalismo consciente": Alexander McCobin. R. ASTARITA, Y TEORÍA SOBRE PLUSVALIA IMPERIALISTA,...DE LUKY DE MÁLAGA,..¡¡...

- Se incluyen resultados de sobre el multicapitalismo mancomunado mundialmentelukyrh blogspot re

volución de la humanidad. ¿Quieres obtener resultados solo de SOBRE EL MULTICAPITALISMO ANCOMUNADO MUNDIALMENTE/LUKYRH.BLOGSPOT.COM-REVOLUCION DE LA HUMANIDAD?

| 17:13 (hace 0 minutos) |   | ||

| ||||

PREFACIO

PREFA: EL IMPACTO DE CHINA EN LAS REGIONES ESTRATÉGICAS

Erik Brattberg y Evan A. Feigenbaum

La huella económica y política de China se ha expandido tan rápidamente que muchos países, incluso aquellos con instituciones estatales y de la sociedad civil relativamente fuertes, han luchado por lidiar con las implicaciones. Ha habido una creciente atención a este tema en los Estados Unidos y las democracias industriales avanzadas de Japón y Europa Occidental. Pero los países "vulnerables", aquellos donde la brecha es mayor entre el alcance y la intensidad del activismo chino, por un lado, y, por el otro, la capacidad local para gestionar y mitigar los riesgos políticos y económicos, enfrentan desafíos especiales. En estos países, las herramientas y tácticas del activismo y las actividades de influencia de China siguen siendo poco conocidas entre los expertos locales y las élites. Mientras tanto, tanto dentro como fuera de estos países, la política transpone con demasiada frecuencia las soluciones occidentales y no está bien adaptada a las realidades locales.

Esto es especialmente notable en dos regiones estratégicas: Europa Sudoriental, Central y Oriental; y Asia meridional. El perfil económico y político de China se ha expandido inusualmente rápido en estas dos regiones, pero muchos países carecen de un banco profundo de expertos locales que puedan hacer coincidir el análisis de las implicaciones internas del activismo chino con las recomendaciones de políticas que reflejen la verdad política y económica interna.

Para abordar esta brecha, la Fundación Carnegie inició un proyecto global para comprender mejor las actividades chinas en ocho países "pivotes" en estas dos regiones estratégicas.

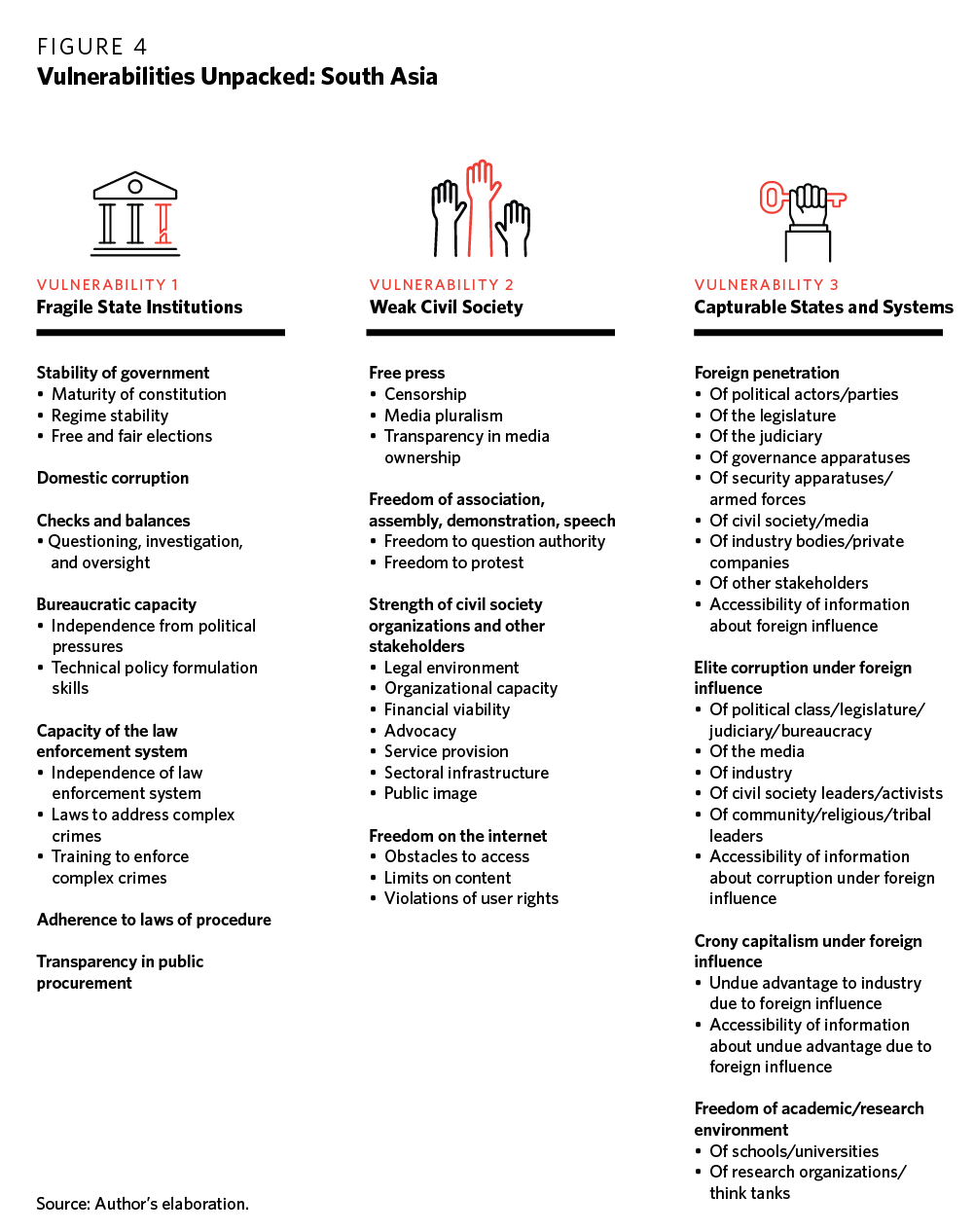

El primer objetivo del proyecto fue mejorar la conciencia local sobre el alcance y la naturaleza del activismo chino en estados con (1) instituciones estatales débiles, (2) sociedades civiles frágiles o (3) países donde la "captura de élite" es una característica del panorama político.

En segundo lugar, el proyecto tenía por objeto fortalecer la capacidad facilitando el intercambio de experiencias y mejores prácticas a través de las fronteras nacionales.

En tercer lugar, el proyecto buscaba desarrollar prescripciones de políticas para los gobiernos de estos países, así como para los Estados Unidos y sus socios estratégicos, para mitigar y responder a actividades que no atentan a la independencia política o al crecimiento económico y el desarrollo bien equilibrados.

Para establecer una imagen completa de las actividades de China y su impacto, este proyecto profundizó en el activismo chino en cuatro países de cada región, ocho países en total.

Comenzamos realizando talleres, para que personas influyentes de todos los países pudieran compartir experiencias y comparar notas. Los participantes invitados incluyeron formuladores de políticas, expertos, periodistas y otros, todos con un profundo conocimiento local, inmersos en la política, las economías y la sociedad civil de sus países. En Europa, los cuatro países fueron Georgia, Grecia, Hungría y Rumania, y en el sur de Asia, Bangladesh, Maldivas, Nepal y Sri Lanka. Las discusiones internacionales entre estos participantes regionales tuvieron como objetivo crear conciencia, discutir las implicaciones del creciente activismo de China en sus países y comparar notas sobre las diversas formas en que estos diversos países habían manejado la rápida afluencia de capital, programas, personas, tecnología y otras fuentes de influencia chinas.

After holding several workshops for each region, Carnegie scholars conducted extensive interviews and a comprehensive review of open-source data and literature on Chinese activities—including extensive media monitoring in local languages, from Nepali to Bengali, Georgian to Greek. These deep dives aimed to measure Chinese influence along three dimensions:

- Chinese activities that shape or constrain the choices and options for local political and economic elites;

- Chinese activities that influence or constrain the parameters of local media and public opinion; and

- China’s impact on local civil society and academia.

The first of these three dimensions is important because China’s sheer size means that it will inevitably play a role in these two strategic geographies. China is the world’s largest trader and manufacturer—and it sits on a significant pool of foreign exchange reserves and capital that countries in all three regions will invariably wish to tap. For this reason, these surveys aimed to identify, distinguish, and analyze only those specific activities that could constrict options, reduce the scope of choice, and reward a narrow interest group or elite.

The second of the three dimensions is crucial because China frequently couples its use of economic and political carrots and levers to broad-ranging public relations outreach. When China floods a country not just with investment but also with strategic messages designed to influence public opinion, there is often little space left for counter-narratives, especially in countries that lack independent media or have weak civil societies.

The third of the three dimensions is critical because in the most vulnerable countries of these two regions, civil society and academia are often too fragile to provide balanced coverage of the activism of external powers. In some cases, Chinese funding and so-called united front tactics have shaped domestic narratives.

Beijing, like other outside powers, cultivates friendly voices in nearly every country. But in some countries, there are few counterweights.

By exploring all three dimensions of Chinese influence simultaneously, Carnegie’s initiative has aimed to generate a clearer and well-balanced picture of Chinese activism and messaging in Europe and South Asia, while fostering a cross-national network of influencers who will continue to compare notes, learn across national boundaries, and spur a genuinely regional conversation about China’s rise and its far-reaching implications.

SUMMARY

El rápido ascenso global de China ha creado nuevos desafíos para los Estados Unidos, la Unión Europea (UE) y los gobiernos europeos individuales. Beijing ofrece una alternativa a Occidente y ofrece soluciones listas para usar a los países que buscan desarrollo económico. Sin embargo, China también se aprovecha de las vulnerabilidades y debilidades locales, como las frágiles instituciones estatales, la captura de la élite y la débil sociedad civil, para ejercer su propia influencia económica, política y de poder blando. Una región donde Beijing ha hecho avances significativos es el sudeste, centro y este de Europa. Para China, esta región es particularmente interesante como punto de entrada al resto de Europa para la Iniciativa de la Franja y la Ruta (BRI), con oportunidades de crecimiento para las empresas chinas y con condiciones regulatorias y económicas más favorables que en Europa Occidental.

Si bien la creciente presencia de China en el sudeste, centro y este de Europa puede traer oportunidades socioeconómicas, también puede exacerbar las deficiencias de gobernanza, socavar la estabilidad política y económica y complicar la capacidad de la UE para llegar a un consenso sobre cuestiones clave. Cómo los países gestionan sus vulnerabilidades y desarrollan resiliencia en sus interacciones con China es el enfoque clave de este documento. Examina cuatro países en el sudeste, centro y este de Europa: Grecia, Hungría, Rumania y Georgia, quienes, a pesar de su diversidad, comparten ciertas características comunes que afectan sus relaciones con China, como el afán por impulsar el comercio y la inversión de China. Si bien no los cuatro países comparten vulnerabilidades idénticas, y aunque China ha tenido más éxito en algunos países que en otros, cada estudio de caso ofrece lecciones prescriptivas sobre cómo los países pueden manejar las vulnerabilidades de diferentes maneras.

Las metas y objetivos de las actividades de China en los cuatro países pueden describirse en términos generales como triples: impulsar las exportaciones e inversiones chinas, ejercer influencia política y fomentar una imagen positiva de China y las relaciones con China. Los cuatro países del caso son parte de la masiva Iniciativa de la Franja y la Ruta de China. Por ejemplo, en Grecia, el gigante naviero chino COSCO ha adquirido una participación mayoritaria en el Puerto de El Pireo para crear un centro regional de transporte y logística en el Mediterráneo como parte de la ruta marítima de la BRI. El modelo de negocios de China prospera en entornos donde las instituciones locales y los marcos regulatorios son débiles y donde los líderes políticos y empresariales locales están ansiosos por beneficiarse de la falta de escrutinio público y transparencia que a menudo acompaña a las inversiones chinas. Un buen ejemplo de esto es Hungría, donde la falta de escrutinio público o transparencia beneficia tanto a China como a las élites locales, alimentando aún más la corrupción local y la cleptocracia.

Además, si bien China puede tratar de tener influencia política en países individuales a través del desarrollo de lazos bilaterales, generalmente está más interesada en aprovechar la influencia política para tener un impacto regional más amplio, como influir indirectamente en el consenso europeo y la alineación transatlántica en temas particulares de interés para Beijing, como los derechos humanos y las situaciones en el Mar Meridional de China. Hong Kong, Xinjiang o Taiwán. Por ejemplo, tanto Grecia como Hungría han acudidos en diferentes ocasiones en ayuda de China para socavar o bloquear las declaraciones de la Unión Europea sobre ciertos temas relacionados con China. Recientemente, en abril y junio de 2021, el gobierno del primer ministro húngaro Viktor Orbán bloqueó las declaraciones de la UE sobre Hong Kong. Sin embargo, mientras que el actual gobierno griego está dispuesto a ser visto como un jugador confiable dentro de la UE y la Organización del Tratado del Atlántico Norte (OTAN), Hungría sigue dispuesta a acudir en ayuda de China, impulsada por el deseo del gobierno de abrir la puerta a las inversiones chinas, obtener apoyo diplomático sobre el retroceso democrático de Hungría y comunicar las alternativas políticas y económicas de Hungría a Bruselas.

En diversos grados, Beijing ha participado activamente en la región para fomentar una imagen positiva de sí mismo, promover su modelo político y económico y dar forma a las narrativas locales sobre las relaciones con China en los cuatro países. La presencia de una sociedad civil débil y la influencia y el control oligárquico sobre los medios de comunicación y las organizaciones no gubernamentales (ONG) también pueden brindar oportunidades para que China intervenga y llene el vacío. Si bien China se involucra en algunos esfuerzos de poder blando, como intercambios entre pueblos y actividades culturales, la mayoría de estos son relaciones a pequeña escala o heredadas con poca relevancia actual. Recientemente, la pandemia de COVID-19 brindó a China nuevas oportunidades para avanzar al proporcionar asistencia muy necesaria en forma de equipos médicos, productos farmacéuticos y, finalmente, suministros de vacunas.

Sin embargo, en lugar de tratar de ganar corazones y mentes más ampliamente, los esfuerzos de poder blando de China se dirigen principalmente a ciertas élites influyentes clave en los negocios, la política, la academia o las ONG. Los Institutos Confucio chinos y las asociaciones académicas en los cuatro países tienden a ser a pequeña escala, pero la construcción masiva planificada de un campus de la Universidad de Fudan en Hungría, si se completa, constituiría una mejora importante en la presencia de poder blando de China en un momento en que la libertad académica en el país ya está en declive. A diferencia de otras partes de Europa, donde China se ha involucrado últimamente en las llamadas tácticas de diplomacia de guerrero lobo, ninguno de los cuatro países del caso ha experimentado una diplomacia china excesivamente agresiva o operaciones de influencia masiva en las redes sociales. Aun así, las percepciones públicas de China se han deteriorado en toda la región (como también lo han hecho en otras partes de Europa), aunque Grecia y Hungría todavía se encuentran entre los países más amigables con China en Europa.

Despite China’s increased role in the region in recent years and the presence of local vulnerabilities that China can exploit to its advantage, there are several points of resilience that limit China’s influence in the four case countries. For instance, while many countries in the region looked to China as an important economic and political partner after the global financial crisis more than a decade ago, they have gradually become disillusioned with Beijing’s ability to deliver on its promises or the specific terms of certain investment deals. As a result, two of its showcase initiatives, the BRI and the 17+1 format, are increasingly perceived by local governments as a vehicle for Beijing to exert political influence with few tangible results to show for. Political shifts in some European countries have also recently replaced more China-friendly parties with governments that are more skeptical of China and keener on reaffirming ties with the United States and the EU. In other cases, Chinese projects have been interrupted by pushback from local and subnational actors such as trade unions or municipal politicians.

Moreover, China’s soft power efforts appear to have had fairly little impact on improving China’s image in the region. In countries with vibrant media landscapes, China’s influence on shaping local debates and narratives is quite limited. Even in countries where perceptions of China were largely positive or neutral, opinions have soured in recent years, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accounting for the limited impact of Chinese soft power in the region is, first, the limited interest in China and its model especially from young pro-Western people. In addition, it is also possible that China’s inability to deliver on its economic promises, the growing international criticism of Beijing’s domestic and foreign policies, and China’s perceived role in the pandemic have all reduced the effectiveness of its public diplomacy. Even as China has stepped in to provide medical supplies and vaccines, overly politicized Chinese assistance has also prompted more hostile diplomatic and propaganda tactics.

El análisis de este documento identifica lecciones prácticas y prescribe soluciones para los responsables políticos de los Estados Unidos y la UE para ayudar a los estados vulnerables a gestionar mejor los desafíos de una rápida entrada de dinero y los esfuerzos relacionados para ejercer la influencia política, económica o de poder blando de China. El estudio también busca ayudar a los estados regionales y a los analistas locales a comprender y navegar mejor los problemas que rodean el enfoque de China hacia el sudeste, centro y este de Europa.

Recomendaciones a los Estados Unidos, la UE y los países de la región:

- Evite representar el sudeste, centro y este de Europa como un caballo de Troya chino

- No exagere la influencia económica de China

- Comprender mejor los intereses locales

- Evite asignar importancia estratégica a todas las acciones de China

- Promover la buena gobernanza y desarrollar la resiliencia local

- Fortalecer la capacidad de la sociedad civil

- No te concentres demasiado en el poder blando

- Estar presente y ofrecer alternativas

- Responsabilizar a Orbán y sus compinches

- Aproveche el atractivo occidental

- Asegurar a los estados más pequeños que Occidente tiene mucho que ofrecer

- Negar aperturas diplomáticas a China

INTRODUCCIÓN

A medida que la huella de China en Europa se ha expandido en la última década, muchos países, incluso aquellos con instituciones estatales y de la sociedad civil relativamente fuertes, han luchado para lidiar con las implicaciones y consecuencias. Europa Central y Oriental (a veces denominada CEE), así como Europa sudoriental, a menudo se considera particularmente vulnerable a la influencia política, económica o de poder blando de China. Los responsables políticos de los Estados Unidos y la Unión Europea han expresado a veces su preocupación de que la influencia de China en esta región podría ayudar a exacerbar los déficits de gobernanza, socavar la estabilidad política y económica y complicar la capacidad de la UE para llegar a un consenso sobre cuestiones clave.

Después de la crisis financiera mundial de 2008, muchos países de la región consideraron a China como un socio económico y, a veces, político cada vez más importante. Con la esperanza de que China pudiera ayudar a impulsar las economías en problemas, los actores locales firmaron múltiples acuerdos y acuerdos con Beijing, a menudo acompañados de diplomacia, pompa y ceremonia altamente elaboradas, con expectativas irrealistamente altas. En particular, la extensa Iniciativa de la Franja y la Ruta de China prometió oportunidades comerciales y de inversión en áreas como infraestructura, transporte y energía. Los países se inscribieron fácilmente en lo que ahora se llama el formato 17 + 1 para convertirse en socios comerciales preferidos con Beijing. Ejemplos notables de inversiones chinas en la región incluyen el Puerto de El Pireo en Atenas y un proyecto ferroviario que une Budapest y Belgrado.

Several reasons account for China’s growing interest and activity in Southeastern, Central, and Eastern Europe. First, the region can serve as an entry point into the rest of Europe for BRI land and maritime projects. Second, it is less economically developed than Western Europe. Its dependence on foreign investment means greater opportunities for Chinese firms to win infrastructure bids and ultimately acquire critical assets. Third, local regulations and economic conditions are typically more favorable for Chinese companies compared to Western Europe, where transparency and accountability mechanisms present bigger hurdles. Finally, China can also leverage local ties to influence EU decisionmaking or undermine EU unity on certain issues, as well as build legitimacy for the Chinese regime back home.

Fast-forward a decade and the situation looks far more complicated. While many countries in the region are still keen to receive Chinese trade and investment opportunities, Beijing’s track record has disappointed all sides for several reasons. First, while the 17+1 format is a useful way for China to engage with multiple individual countries, it never became a platform to advance Chinese interests broadly in the region. In fact, in many places, it has turned out to be an empty diplomatic shell, with summits and declarations but few clear policies. Six regional leaders skipped the most recent 17+1 summit in early 2021, which was chaired for the first time by Chinese President Xi Jinping himself, demonstrating a growing apathy toward the format. Second, frustration and discontent are mounting over the terms of specific Chinese investment deals in many of the regional states. There have been some high-profile deals, but they remain controversial and have not lived up to expectations that they would bring sustainable jobs and growth objectives. Third, political shifts in some European countries mean that seemingly pro-Chinese parties or politicians have been replaced at the ballot box with leaders more skeptical of China, who have canceled nascent deals. Fourth, several (though not all) of the countries in the region have pivoted away from China and back toward the United States and the EU in recent years, due to existing security partnerships and pressure from Washington and Brussels. The United States’ growing preoccupation with its rivalry with China has translated into increased pressure on regional European governments to reduce their dependence on Beijing and toe the line on issues such as 5G, Chinese ownership of ports and other strategic infrastructure, and investment screening. Similarly, the EU—increasingly wary about Chinese efforts to divide the EU with initiatives like the 17+1 format and the Belt and Road Initiative—has identified China as a partner, an economic competitor, and a systemic rival.1 Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted both the risks and the opportunities of China’s enhanced regional role. Even as China has stepped in to provide medical supplies and vaccines, overly politicized Chinese assistance has also prompted more hostile diplomatic and propaganda tactics.

This paper examines Chinese influence in four regional countries: Greece, Hungary, Romania, and Georgia. Much of Beijing’s activity in these four countries, as elsewhere in the world, can be characterized as regular commercial trade, which is broadly welcomed. The focus of this paper is on cases where Chinese influence has seemingly undermined democratic processes, fostered or taken advantage of corrupt practices, or been harnessed to a local political agenda.

Despite their diversity, all four countries share certain common characteristics that affect their relations with China. They have all been eager to attract Chinese investment to help jump-start job growth, reduce poverty, and build new infrastructure. In addition to infrastructure investments across the region, China has also invested in the energy and transportation sectors. For some countries, that influx of Chinese finance has added to their debt load.

Hit hard by the eurozone debt crisis, Greece, where China has extensive stakes in the Port of Piraeus, is the most recent member of the 17+1 club, joining the format in 2019. One of Eastern Europe’s biggest economies and a former ally in a previous era during the reign of Communist Party dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu, Romania followed this track initially but has grown more cautious. Disillusionment with Chinese investments and fraught domestic politics have blunted Beijing’s aspirations. Although not a member of NATO or the EU, Georgia enjoys a close security and political relationship with both through its long-standing participation in the alliance’s Partnership for Peace program, as well as its association and free trade agreements with the EU. Yet Tbilisi too looked toward China for help, signing a free trade agreement with Beijing, developing much needed infrastructure projects and seeking a counterbalance against an aggressive Russia to its north. Georgian hopes of a new Chinese partnership have dimmed, however. On big political issues Beijing tends to favor Moscow over Tbilisi, while Chinese investment to date has been smaller than many anticipated and often clouded by a lack of transparency.

On the other side of the spectrum is Hungary, where China has developed its closest partnership in Europe. As Hungary slides toward authoritarianism, the government of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has embraced Beijing, allowing China to leverage pro-government local media and NGOs. The Hungarian government initially welcomed with open arms the proposal to establish a massive Fudan University campus in Budapest—the first outside China—although many Hungarians have pushed back at the project and the project’s future now is uncertain. Hungary has become a leading voice within the EU for closer relations with Beijing, having also opposed joint EU positions on several occasions, particularly when it concerned human rights issues.

METHODOLOGY

Greece, Romania, Georgia, and Hungary were selected for this study because they each share at least one of three characteristics that leave them potentially exposed to malign Chinese influence:

- State institutions are weak, making it harder to vet or monitor Chinese economic or political activities. Examples include poor investment screening mechanisms and weak regulatory, law enforcement, anti-corruption, or judicial agencies.

- Captured or “capture-able” states and systems, in which the political apparatus and/or civil society are subject to foreign penetration. Chronic crony capitalism, where elites have embraced China for personal or financial gain, has facilitated Chinese political influence, as have underfunded research institutions that accept Chinese funding, to provide Beijing-friendly voices and help justify questionable business arrangements.

- Civil society has relatively few independent voices, and independent media often lacks the power to expose instances of corruption and other wrongdoing.

While not all four of these countries share the same vulnerabilities, each case study offers prescriptive lessons, even when China is not intensely active or successful. Countries that manage those vulnerabilities in different ways can help teach others by sharing and comparing their experiences. For example, while three of the four countries are members of both the EU and NATO as well as the 17+1 format, nonmember Georgia, which has shown an interest in developing its ties with China, was included because it provides a useful comparison of Chinese tactics and successes across the broader region.

In terms of research methodology, this paper measures Chinese influence along three crucial dimensions:

- Activities that shape or constrain the choices and options for local political and business elites

- Activities that influence or constrain the parameters of media and public opinion

- China’s impact on local civil society and academia

For each of the four case studies, the paper poses the following critical policy questions:

- What underlying strategic logic and objectives drive China’s activities?

- What vulnerabilities and weaknesses has China been able to leverage—and by what means (that is, political, economic, technological, or informational tools)? How well coordinated is China’s use of these various tools and efforts?

- How effective are Chinese influence activities? What impact do they have on local institutions and public or elite perceptions?

- What threats does a Chinese economic profile that fosters dependence and constricts choices pose to the interests of the United States, its allies, and partners? What about direct efforts to exert influence on domestic politics?

- Has China played an important role in supplying medical equipment or COVID-19 vaccines? How has China been involved in regional economic recovery during and after the pandemic?

- How have these countries managed and mitigated their vulnerabilities? What lessons can other countries draw from their experiences?

The analysis in this paper identifies practical lessons and prescribes solutions for policymakers from the United States and the EU to help vulnerable states better manage the challenges of a rapid inflow of money and related efforts to exercise political, economic, or soft power influence from China. The study seeks to help regional states and local analysts better understand and navigate the issues surrounding China’s approach toward Southeastern, Central, and Eastern Europe.

GREECE: STILL THE DRAGON’S HEAD?

Since 2015, Greece has been seen as one of China’s closest allies in Europe. Chinese companies have made two significant investments there. Piraeus harbor, at the core of the Greek economy, is now managed by a Chinese state-owned enterprise. Xi has referred to it as the “dragon’s head” of the Maritime Silk Road.2 Greek leaders have played along, visiting China frequently and, on some occasions, adjusting their foreign policy to please Beijing. In Thessaloniki, Greece’s second harbor, another Chinese company—China Merchants—has also been playing a key management role although not holding a majority share. Meanwhile, China has developed a positive narrative toward Greece, using media, culture, and education as tools of influence. Chinese officials have also paid multiple trips to Athens, culminating in Xi Jinping’s state visit in November 2019.

Still, in recent months, there has been a visible shift in Greece’s stance toward China. Domestic debates have grown tense and complex. Beijing offered modest help during the pandemic (and made sure the Greek public knew about it). Although the Chinese press depicts Sino-Greek relations in a positive light, Greeks no longer see China as a savior for their economy. In fact, polls show an increasingly defiant Greek public. The country’s conservative government, elected in mid-2019, has reaffirmed Greece’s strong commitment to the EU and NATO, and recent surveys suggest the public supports that stance.3 The cabinet of Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis retained the EU’s triad definition of China as a partner, an economic competitor, and a systemic rival, and it has reaffirmed its full support for the transatlantic alliance, notably during former U.S. secretary of state Mike Pompeo’s visits in October 2019 and September 2020.

China’s flagship investment project in Piraeus has also become mired in conflicting local interests and controversies. Twelve years ago, Greece was opening its arms to China. Now, a combination of shipowners, trade unionists, and local politicians is openly rallying against the port’s main shareholder. Things could change again if Greece’s economy deteriorates further following the pandemic. With the absence of tourists and slower business, Greece’s renewed vulnerability could make it a target for China. Facing a wave of blockages across Europe, Chinese companies in the maritime sector are currently sitting on the fence waiting to see what will come next in Southern Europe after the COVID-19 pandemic.

A BRIEF HISTORY

Chinese records describe early encounters between the Chinese and Greek civilizations as early as the reign of King Alexander the Great (336–323 BC), making the Sino-Greek relationship perhaps one of the oldest between an ancient European nation and imperial China.4 For all the niceties of antique imagery, though, they do not automatically unite the two countries in the twenty-first century. In Greece, some have called the relationship with China “a nostalgic look at a vaunted past,” which may reflect the country’s bitterness in the aftermath of a severe debt crisis as well as the need for renewed self-confidence.5 For a decade or so, it appeared a honeymoon between the heirs of glorious Athens and an assertive Chinese Communist Party suited both nations’ interests. Greece has been associated with the “Maritime Silk Road of the 21st Century” described by Xi in his October 2013 speech in Jakarta (weeks after he detailed the Land Silk Road in Astana), and it is now presented by China as a key supporter of the global BRI project.6

The Republic of Greece and the People’s Republic of China established diplomatic relations relatively late, in 1972.7 For years, center-right parties in Greece kept political ties with Beijing to a strict minimum, reflecting a strong traditional divide between the left and the right as well as a polarized attitude toward the United States that formed in the Cold War era. Former prime minister Andreas Papandreou, of the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK), was the first modern Greek leader to visit Beijing in 1986, followed by then Chinese premier Zhao Ziyang’s visit to Athens. Warmer relations followed. The hosting of successive—and successful—Olympics in Athens (2004) and Beijing (2008) brought the two governments even closer. For years, China had to make its first organized Olympics the most symbolic international event ever staged as part of the country’s renaissance. As the original Olympic nation, Greece was keen—and certainly flattered—to cooperate with China on this issue.

Around 2006, then prime minister Kostas Karamanlis’s conservative government decided to liberalize port services to boost competitiveness. China quickly took a commercial interest in the Port of Piraeus, one of the Mediterranean Sea’s best located harbors, with connections to the Near East, Southern Europe, and North Africa. That same year, Karamanlis visited China and the two governments agreed to enter a dialogue “to provide facilitation for the cooperation between administrators of port affairs as well as other administrators in transportation, security and port building in the two countries.”8

It did not take long for the Chinese state to purchase Greek bonds worth some $6 billion after the 2008 financial crisis. China also expressed interest in various infrastructure projects—especially in the Greek maritime sector, relevant to its own maritime global strategy as well as trade interests toward the European continent. Since the Hu Jintao era (2002–2012), China had been planning to become a strong maritime nation; the conveniently located Piraeus Port was a logical hub for Chinese shipping activities and trade in the region.

In November 2008, the Greek state reached a concession agreement for Piers 2 and 3 with the port management division of state-owned China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO)9—at the time the world’s seventh-largest container shipping company.10 The state-controlled Piraeus Port Authority (PPA) and COSCO agreed to a thirty-five-year lease for the concession of Piers 2 and 3. Eight years later, a $431 million investment led to COSCO becoming the majority shareholder of the PPA, with 51 percent of the stock listed as of April 2016 and a commitment for further investments. In the meantime, the financial crisis had brought China and Greece even closer as the Southeastern European country was steered by the international troika of creditors—the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund—to accept massive financial support through three successive bailout agreements.

To cure Greece’s financial woes, international creditors imposed the privatization of state assets in addition to major structural reforms and belt-tightening. Despite the Greek electorate’s deep frustration over the latter, the Syriza-led left-wing coalition elected in 2015 had no choice but to follow suit.11 This was also the case regarding the Piraeus agreement.12 De hecho, el gobierno de coalición de izquierda se dio la vuelta y optó por jugar la carta de la inversión en China, tal vez incluso con más fuerza que su predecesor. Por ejemplo, el entonces primer ministro Alexis Tsipras sorprendió a sus homólogos europeos en julio de 2016 cuando bloqueó una declaración de la UE que apoyaba la decisión de la Corte Internacional de Arbitraje de fallar en contra de China en un caso presentado por Filipinas con respecto al Mar Meridional de China.13 Un año después, diplomáticos griegos bloquearon otra declaración de la UE en las Naciones Unidas (ONU) que criticaba el empeoramiento del historial de derechos humanos de China. La decisión de Tsipras fue descrita como un movimiento oportunista (o tal vez como una herramienta de negociación con Beijing) por los aliados y comentaristas occidentales.14

Sobre el terreno, el acuerdo de COSCO en El Pireo no era una conclusión inevitable. La compañía china fue recibida inicialmente en los muelles con pancartas que decían "COSCO go home" exhibidas a lo largo de la costa y una huelga de noventa días de trabajadores portuarios por parte de los sindicatos portuarios. Los accionistas chinos, en respuesta, adoptaron un perfil deliberadamente bajo. Durante muchos años, el puerto había sido desgarrado por disputas laborales, ya que la tasa de desempleo de Grecia alcanzó el 70 por ciento en los suburbios del suroeste de Atenas, en parte debido al mal desempeño del puerto de El Pireo. Bajo la gestión de COSCO, la fortuna del puerto experimentó un cambio impresionante. La compañía china comenzó a renovar la infraestructura, introdujo más eficiencia y mejoró el estilo de gestión de la autoridad portuaria, lo que contribuyó a un mayor tráfico. Entre 2010 y 2012, el tráfico de transbordo se triplicó con creces.15 Según Sotirios Theofanis, ex director ejecutivo de la Autoridad Portuaria del Pireo S.A., "la razón principal del aumento del tráfico fue la decisión estratégica de China de desviar el tráfico de transbordo a El Pireo".16

Entre 2009 y 2018, el volumen de contenedores de El Pireo pasó de 0,8 millones de contenedores a 4,9 millones (medidos en unidades equivalentes de veinte pies, la unidad estándar de capacidad de carga), con un aumento del 190 por ciento desde 2017.17 Bajo la gestión de COSCO, el puerto de contenedores saltó al puesto número seis en Europa en 2018,18 y el número treinta y dos en el ranking mundial de puertos de 2018 de Lloyd's List.19 En 2016, COSCO formó la llamada Alianza Oceánica con el gigante naviero francés CMA CGM, la Orient Overseas Shipping Line de Hong Kong y la taiwanesa Evergreen Line, que se racionalizó para pasar su tráfico a través del puerto del Pireo.20 Las grandes empresas, como Hewlett-Packard (HP), Sony o (menos sorprendentemente) los fabricantes chinos de equipos de telecomunicaciones Huawei y ZTE, comenzaron a reubicar partes de sus actividades de distribución de otros puertos europeos a El Pireo. En 2013, un acuerdo firmado entre HP, la compañía ferroviaria griega, y COSCO llevó al fabricante de productos electrónicos a enviar mercancías como computadoras portátiles, computadoras de escritorio e impresoras a Grecia, y luego entregarlas en tren o en barco desde El Pireo a otros puertos en los mares Negro y Mediterráneo.21 HP, que había estado utilizando El Pireo como una de sus principales puertas de entrada de carga marítima para el sudeste y el centro de Europa, esperaba ahorrar costos a largo plazo utilizando el transporte ferroviario desde El Pireo para su distribución a los Balcanes, Hungría y la República Checa.22 Pero un factor crucial, el ambicioso proyecto ferroviario de China que une Budapest con Belgrado y, en última instancia, con El Pireo, ha tardado mucho más en materializarse de lo planeado originalmente.

EL PUERTO EN EL CENTRO DE LA RELACIÓN SINO-GRIEGA

Durante los últimos doce años, la relación entre China y Grecia ha girado en torno al Puerto del Pireo y el papel que Beijing espera desempeñar en la región mediterránea bajo la BRI. Desde que COSCO puso un pie oportunistamente en Grecia, la inversión china allí ha sido una fuente de orgullo en los medios de comunicación chinos.

Bajo el acuerdo de 2016, Grecia acordó otorgar a COSCO una participación adicional del 16 por ciento del PPA para 2021, siempre que la compañía china completara inversiones obligatorias por valor de $ 342 millones. Estas inversiones adicionales incluirían un nuevo muelle de cruceros, una zona de reparación de buques, un centro logístico y una terminal de automóviles, así como instalaciones hoteleras para atraer a un mayor número de turistas chinos.23 Ese aspecto de hospitalidad ha sido un elemento importante del plan chino, especialmente desde que se establecieron los vuelos directos de Beijing a Atenas en Air China en 2017. Sin embargo, durante la pandemia de COVID-19, todos los vuelos quedaron en tierra. Los dos gobiernos ahora están buscando con cautela relanzar oficialmente el turismo chino en Grecia en 2022. Es probable que el operador de viajes Thomas Cook, propiedad de Fosun International, con sede en Shanghai, desempeñe un papel importante si Grecia permite que los cruceros chinos regresen a la zona. El turismo, que se ha visto gravemente afectado desde principios de 2021, sigue siendo una industria importante para Grecia.

Pero los problemas clave están en otra parte. A mediados de 2021, según el Ministerio de Transporte Marítimo y Política Insular de Grecia, solo el 58 por ciento de las inversiones obligatorias han sido completadas por COSCO y su subsidiaria, Piraeus Container Terminal S.A. (PCT). En particular, algunas de las inversiones, incluida la nueva terminal de cruceros, que será construida por un contratista griego local seleccionado por COSCO a través de una licitación, se beneficiarán de los fondos estructurales europeos.24 Políticos locales, armadores y sindicatos se han manifestado contra COSCO. En la vecina ciudad de Perama, que se beneficiaría de la mejora de la infraestructura y el equipo, hay decepción de que el área haya permanecido como un remanso.25 Las empresas de reparación naval se han opuesto firmemente al plan de COSCO de construir un nuevo astillero en Perama,26 que no formaba parte del contrato original y podía perjudicar a los astilleros griegos existentes.

Los armadores, que proporcionan barcos fletados a las líneas navieras chinas y son grandes clientes de la industria de la construcción naval china, se quejan del acceso al mercado en la propia China. "Por un lado, COSCO está desesperado por mejorar su huella en el sudeste de Europa, por otro lado, no existe la igualdad de condiciones en China", dijo un operador naviero, quien destacó "la arrogancia de los funcionarios de COSCO".27 Los armadores griegos dicen que todavía controlan una flota del doble del tamaño de la de China y no ven una inversión de roles en el futuro cercano. Aún así, en 2017, la Administración Oceánica Estatal de China (SOA) enfatizó que el producto interno bruto (PIB) marítimo del país representaba aproximadamente el 10 por ciento del PIB general de China.28 Por lo tanto, no es una sorpresa que hacer de China una nación marítima haya sido un objetivo nacional desde el XIX congreso del Partido Comunista, que elevó la construcción de una "nación marítima fuerte" al "más alto nivel".29

Unos meses después de que el partido Griego Nueva Democracia ganara las elecciones de 2019 bajo Mitsotakis, los medios griegos informaron de un número creciente de temas controvertidos con respecto a la inversión de COSCO. Estos incluyen la ausencia de una evaluación de impacto ambiental para la construcción de la nueva terminal de cruceros, y los riesgos de que la transferencia de escombros en la ciudad pueda causar congestión y contaminación.30 Otro tema de discusión ha sido la propuesta de COSCO de establecer el Sistema de Comunidad Portuaria Helénica (HPCS), una plataforma electrónica de gestión multifunción para el Puerto de El Pireo. Después de acaloradas discusiones, el Ministerio de Transporte Marítimo griego introdujo una nueva ley que reemplaza HPCS con el Sistema Nacional Integrado de la Comunidad Portuaria de propiedad estatal.31

The Piraeus Chamber of Commerce and Industry, representing local businesses, appears to have become highly skeptical of COSCO. There are growing concerns that part of the shipbuilding orders might move to Chinese shipyards.32 During a Piraeus city council special session on November 20, 2020, shipowner Vangelis Marinakis expressed his strong opposition to the Chinese company’s extension plans, stating bluntly that “Piraeus can expect no benefit from COSCO.”33 He was supported by several political parties, along with environmental groups who have rallied against the company’s plan to build a fourth pier on reclaimed land. Later, China’s ambassador to Greece, Zhang Qiyue, tried to save the deal by stepping in for COSCO. In March 2021, however, she was promptly recalled to Beijing—apparently due to the lack of progress.34

Instead of building a new pier, COSCO might now try to invest in additional equipment to increase handling capacity in Pier 1 to maintain Piraeus’s ranking for the next few years.35 It appears local actors have also refused to pay entry fees imposed by the COSCO-run PPA for commercial vehicles, even though these were part of the original global concession agreement between COSCO and the Greek government. “Currently, there is no fertile ground for an extension of Chinese presence,” said Rui Pinto, deputy chief executive of the Thessaloniki Port Authority.36 COSCO’s plan to build a car terminal in an area used by local ship-repair businesses has also encountered heavy criticism from locals, who fear it would be contrary to the interests of Greek shipyard owners.

Current tensions reflect the fragility and emotional aspects of the Piraeus deal in the eyes of both the shipping industry and local communities. But as Greek resistance to the Chinese presence rises (sometimes influenced by outside players such as the EU or the United States), Chinese media sources consistently insist on the “Sino-Greek engagement over long-term Chinese investment,”37 reflecting a true contrast between Greece’s and China’s assessment of their bilateral relationship. Recent media coverage on each side could hardly be more different.

BEYOND PORTS

Though port business may be highly profitable, it is also very competitive in the region. Other Mediterranean harbors have started to catch up, beginning with Morocco’s Tanger Med (which now ranks higher than Piraeus38) and Spain’s Valencia, not to mention the formidable alliance operation between Antwerp and Zeebrugge farther north.

China has attempted other inroads into the Greek market. For example, another port operator, CMPort—part of the China Merchants conglomerate—has been involved in Thessaloniki, Greece’s second-largest port, through Terminal Link, a joint venture with France’s CMA CGM.39 The former chief executive of Terminal Link, Boris Wenzel, also invited CMPort to install its terminal operating system at Thessaloniki.40 However, because the two Greek facilities are managed as completely separate businesses, they do not constitute a global investment strategy on the part of China.

Besides Piraeus and Thessaloniki, China’s business presence in Greece has stumbled. One of China’s largest commercial banks, Bank of China, proudly opened its Athens branch in late 2019, pledging to make greater contributions to the BRI by providing “professional and efficient financial services for Chinese ‘go global’ companies and use financial power to build a bridge for cross-border business between Greece and China.”41 The banking business, however, has flagged, in line with the global economic slowdown. Like many Chinese institutions, Bank of China is playing a long-term game and hopes to benefit from deeper interactions between Greece and China. For the time being, though, it has been a low-key operation—quite the opposite of China’s original goal.

Several Sino-Greek business deals have also been interrupted, if not outright canceled. In 2016, COSCO surprisingly stayed out of the race to privatize Greece’s railway operator TrainOSE, despite Premier Li Keqiang’s earlier interest. In 2018, the National Bank of Greece severed its negotiations with Gongbao for the sale of Ethniki Asfalistiki, the country’s largest insurance company.42 Five years after signing a $200 million investment agreement, real estate and financial group Fosun International withdrew in 2019 from a massive project to develop the former Hellenikon airport, apparently due to “years of delays caused by red tape and the country’s economic crisis.”43 Tellingly, the Chinese consortium was not entitled to bid for a gambling license that was eventually awarded to the U.S.-based Mohegan group and Greek construction company Gek Terna. More recently, in January 2021, the Greek government did not allow China’s State Grid (which already held a 24 percent stake in Greece’s high-voltage Independent Power Transmission Operator) to bid for a 49 percent stake in the country’s mid/low-voltage distribution network operator. Another Chinese state-owned enterprise, South Power Grid, was also disqualified. Lastly, the Greek government is leaning strongly toward non-Chinese suppliers for 5G technology. In March 2021, Cosmote, the largest Greek mobile service provider, selected Swedish telecommunications company Ericsson as its exclusive 5G equipment supplier. Greece also joined the U.S.-led Clean Network, an initiative on 5G launched by former president Donald Trump’s administration.44

HIGH HOPES FOR CHINESE TOURISTS

Despite COSCO’s long-term plan, which should in principle serve as an engine for potential Chinese cruise visitors, Greek tourism sector professionals have had mixed feelings. Of the 28 million foreigners who visited in 2019, the vast majority actually came from Europe and the United States—compared to only 200,000 from China.45 The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has halted travel, and it is likely that Chinese tourists will not be back for some time. The island of Santorini, a huge draw for Chinese tourists, has been badly hit by the absence of international inbound flights. Santorini’s hotels have remained mostly empty, and it is unlikely that the newly branded “Greece-China Year of Culture and Tourism 2021” will bring Chinese tourists back to Greece in significant numbers anytime soon. Similarly, Sino-Greek cultural activities appear to be very limited, according to media coverage studied by the Institute of International Economic Relations (IIER) through 2020 and early 2021.46 This does not bode well for China’s image among the general public.

GOLDEN VISAS

It has been almost a decade since Greece (along with nearby Malta and Cyprus) started luring individual Chinese investors willing to invest about $290,000 or more in a Greek property against the promise of a renewable five-year residence permit, which in theory allows free travel throughout the twenty-seven EU states.47 Foreigners who have spent at least seven years in Greece are able to use their so-called golden visa to obtain a much-coveted EU passport. As of November 2020, 70 percent of golden visa holders were Chinese citizens (5,504 out of 7,903 in total)—and numbers continue to rise. In 2019, foreigners invested some $1.7 billion in the Greek real estate market,48 including Chinese buyers who were able to defy China’s strict capital control rules.49 Following a dire two years due to COVID-19, the Greek government will encourage new schemes in areas with fewer visitors, such as western or northern Greece.50

Meanwhile, the EU continues to criticize Greece’s golden visa program. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen warned in her September 2020 state of the union speech that “European values are not for sale.”51 In addition, local analysts have pointed out that Chinese media almost never mention the golden visa scheme. One explanation for this discrepancy could be that a growing number of Chinese applicants for visas in Greece are effectively communicating their intention to leave China.52 The Chinese government would not want that to be discussed openly.53

CHINA’S DEDICATED SOFT POWER STRATEGY

Before the pandemic, many Greeks seemed grateful for China’s help. The combination of tourists, investors, merchants, and some cultural events—such as the Ancient Civilizations Forum in 2017 or the annual meeting of European Confucius Institutes in 201854—initially helped China win over the Greek public, or at least some Greek elites. This narrative no longer holds. The Greek public seems more interested in real action and jobs.

In 2016, China launched the first ever Business Confucius Institute at the Athens University of Economics and Business, with the clear aim of building stronger business ties between the two countries. There are also classic Confucius Institutes based at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and the University of Thessaly in Larissa. Both are mainly focused on Chinese language studies and avoid controversial issues such as Taiwan or Xinjiang. Much like in other European countries, China-backed organizations—such as the Greece-China Association and the Hellenic-Chinese Chamber—promote business ties between the two countries. Close Chinese contacts with Greek political parties have been irregular, apart from the hardline Greek Communist Party (KKE), which said in 2010 that “it continues to maintain bilateral relations with the [Communist Party of China].”55

Collaboration has also extended to other fields. In 2018, China and Greece signed an action plan for scientific and technological cooperation.56 A Chinese AI application development company, DeepBlue Technology, announced it would start an innovation channel between Greece and China.57 Other impactful plans include a Center for China Studies jointly run by the Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and programs to attract more Chinese students in the years to come. The University of the Aegean has even launched an online facility for Chinese-language classes.58

The BRI is, of course, a permanent feature of China’s presence in Greece. In 2019, then prime minister Tsipras also felt the need to join the 17+1 format, a group of Southeastern, Central, and Eastern European countries that meet annually with top Chinese leadership (although the current Greek government has been much less enthusiastic than its predecessor).59 In the past, Greek officials have often taken part in BRI activities both in Greece and in China. Tsipras himself attended two Belt and Road forums in Beijing, in 2017 and 2019.60 During a separate official visit to China, he declared that Greece intended to “serve as China’s gateway into Europe.”61 His successor, Mitsotakis, has been more subdued, although he hosted Xi in 2019 and has said that he hopes for a “new era in Greek-Chinese relations.”62 Wary of regional tensions with Turkey, the Greek prime minister has also realized how much Greece needs the United States and the EU; China has little to offer in terms of security.

CHINA’S GROWING MEDIA PRESENCE

In terms of media presence, China’s Xinhua News Agency established a bureau in Athens years ago, employing some Greek stringers. It has also engaged in an official exchange with the state-owned Athens-Macedonian News Agency (AMNA) since 2016. The China Economic Information Service, an affiliate of Xinhua, also signed an agreement with AMNA to set up a Belt and Road Economic Information Partnership. In addition, Chinese media outlets have cooperated with Greek newspapers like Kathimerini, which has an English edition and has frequently published editorial dispatches from Xinhua. Greek state television and China’s National Radio and Television Administration signed a memorandum of understanding in late 2019.63 Like many of their colleagues in Southeastern, Central, and Eastern Europe, Greek journalists have been frequently invited to BRI events in China. It is important to note, however, that the Greek public has not benefited from independent coverage of Chinese news because Greek media do not have their own correspondents in China. All in all, that means Greece has been vulnerable to Chinese media narratives for some years. It will remain so, unless it invests in specialized coverage of China or Chinese-European relations.

Through its local presence, Chinese media has been offering an interesting narrative to the Greek public.64 First, it presents China as a “benign superpower, which is promoting a new set of harmonious international relations, based on rapid socio-economic development and ‘win-win cooperation.’” But it also focuses specifically on the Sino-Greek relationship: according to a recent IIER report, China “wants to be seen as a true friend that offers generous assistance to Greece.” Through 2020, Chinese media reports countered any accusations over Beijing’s responsibility for the pandemic with examples of the aid it has delivered to Greece.

THE IMPACT OF CHINESE INFLUENCE IN GREECE

Ever since the 2004 Athens Olympics (and especially since COSCO took over management of Piraeus), China has been courting the Greek public—with some success. Unlike other European countries, Greece has not been the target of China’s aggressive wolf warrior diplomacy (named for a popular Chinese blockbuster movie).65 Again, this softer diplomacy shows that China is playing a long-term game in Greece. As a sign of goodwill, Beijing has tried to remain accommodating and uncontroversial on its embassy’s Facebook and Twitter accounts. The Piraeus Port Authority has also been running soft communication campaigns through its own social media outlets. Although China’s image could be considered neutral in Greece, this moderate approach has yielded mixed results according to several recent surveys of the Greek public.

First, the Athens-based IIER determined that China’s soft power strategy toward Greece was largely successful between 2008 and 2018. According to its report, IIER found that “the general public assesses the relations between the two countries in a very positive light: in December 2016, a vast majority of the respondents (81.9%) qualified them as ‘friendly’ and ‘relatively friendly.’” The same IIER report also found that most Greeks appeared to support closer relations with Beijing regarding the economy (83.5 percent), politics (71.1 percent), and culture (87.5 percent).66 A second study, by the Pew Research Center in 2019, found Greeks, along with Hungarians, to be perhaps the most China-friendly Europeans: 26 percent said the world would be better with China as a leader, while 46 percent said the world would be better with the United States as a leader.67 For comparison, that same year, only 14 percent of respondents from Sweden favored China; 76 percent had more confidence in the United States.

The year 2020 appears to have been a turning point for China’s local perception, not only due to COVID-19 but also because of China’s clumsy attempts to fashion itself as a benefactor. Despite its overtures, the vast majority of medical supplies from China during 2020 were commercial orders rather than gifts. In April 2020, a survey conducted by Kapa Research, a Greek pollster, found that 44 percent of Greek respondents blamed China for the pandemic68—a claim strongly rejected by China’s ambassador in Athens.69

CHINESE OFFICIAL VISITS

Since 2008, visits by senior Chinese officials have multiplied: former president Hu Jintao attended the COSCO signing ceremony at Piraeus in 2008, prime ministers Wen Jiabao and Li Keqiang both paid official visits in 2010 and 2014, respectively, and the regular flow of visitors includes deputy prime ministers, ministers, vice ministers, and the heads of state-owned companies. It is no surprise that Chinese Politburo member and foreign affairs supremo Yang Jiechi’s visit to Athens in September 2020 received more coverage in the Chinese media than in the Greek press. Tellingly, Yang—who was on a diplomatic tour including Myanmar and Spain—called for building Piraeus into a world-class port.70

Chinese media’s positive spin on Sino-Greek relations does not often target the general Greek public. Instead, it’s aimed at business leaders, government elites, or, occasionally, a domestic Chinese audience, like when National Defense Minister Wei Fenghe visited Athens in March 2021. Although possible joint drills and training were discussed, it is highly unlikely that Greece, a NATO country, will engage in military exercises with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Rather, the goal of such a visit is to show to China’s domestic audience that Beijing has international friends willing to cooperate.71

During his own prominent visit in November 2019, Xi referenced COSCO’s presence as a “dragon’s head.”72 The goal, he said, is to make China an even larger player in the Mediterranean. Building on the narrative of kinship between two old civilizations,73 Chinese media reported that Xi and Greece’s then president Prokopis Pavlopoulos had agreed to “contribute the wisdom of ancient Eastern and Western civilizations to building a community with a shared future for mankind”74—this kind of discourse has been well-received among Greek elites.

CONCLUSIONS

Looking at Chinese maps of the BRI, Piraeus is always at the center of the Maritime Silk Road. After all, the construction of a strong maritime power has become a national goal for China, and the Chinese position in Greece is at the forefront.75 Before the pandemic, China initially saw the Piraeus deal as a “historic opportunity” for a declining European economy to “return to the centre of the world through the revival of Eurasia.”76 Like Hungary or several countries in the Balkans, Greece was chosen to be part of a Chinese sphere of influence on the European continent. Thanks to major Chinese investments, that seems to still be a priority.

The outcome of such a policy, however, remains unclear. First, Greece has been busy handling its regional disputes with neighboring North Macedonia and, especially, Turkey. It needs NATO and the EU’s diplomatic and military support to counter Turkey’s militarization of the region surrounding Cyprus. Second, as is often the case with Chinese investment projects, the reality has differed from the initial proposition. “In the grand scheme of things . . . China invested in the port of Piraeus at a time when nobody was interested and it has been a successful investment,” Mitsotakis said in a recent interview. “But,” he went on to say, “Greece is not particularly dependent on Chinese investment, when I look at the map of Foreign Direct Investment, certainly I look at countries that are interested in investing in Greece.”77 Problems continue to accumulate around the Piraeus deal, and locals are more sensitive and angrier than expected about the benefits—or lack thereof—from COSCO’s financial involvement and oft-overbearing presence.

For China’s ambition as a new superpower, the stakes are running high. Despite close contacts with both Russia (through the Russian Orthodox Church) and China, Greece remains firmly anchored in traditional Western institutions and alliances. Finally, the pandemic seems to have engendered the same sense of disappointment in the Greek public as in other Southeast European nations vis-à-vis China. Athens may still have a long way to go before becoming the dragon’s head. Soft power, official visits, and expansion plans have not managed to fill that gap and—for the time being—the Greek people do not want to trade their independence and European ties simply to comply with the grand strategy of Xi’s China. What is clear, though, is that China has engaged in a long-term game regarding Greece, which—despite recent turnarounds—Beijing still views as a valuable hub and partner in Europe. The way China has engaged with the country for almost two decades demonstrates clear commitment to its long-term plan. Both the EU and the United States may have managed to keep Greece on their side for now, but the future remains uncertain if China continues to pursue a strong and ambitious maritime agenda in the Mediterranean Sea and beyond.

HUNGARY: A WILLING CHINESE PARTNER IN THE HEART OF EUROPE

Hungary, having embraced closer ties with China in the early 2000s, is something of an outlier in the EU. It has become one of the most vulnerable countries in the region for Chinese influence under the government of current Prime Minister Viktor Orbán. Hungary’s vulnerability is due to relatively weak state institutions that are largely controlled by an increasingly authoritarian ruling party and the limited voice of civil society. The ease with which Beijing has facilitated elite capture plays an important part in China’s ability to cultivate key decisionmakers, who, in turn, are eager for better relationships with their Chinese counterparts. Orbán, who personally directs the country’s policy toward China, has been in power for over a decade and has troubled relations with his counterparts from Hungary’s traditional Western partners.78 Reportedly, Orbán views the Chinese government—which prioritizes the principles of state sovereignty and nonintervention in the domestic affairs of its diplomatic partners—as an alternative to the liberal West, where his counterparts have been highly critical of Hungary’s democratic backsliding.79 He and other prominent Hungarians speak warmly of China’s economic development model.

For Budapest, Beijing became a key partner for diversifying its economic policy away from Europe after the 2008 global financial crisis. Over time, Orbán has begun to shift Hungary’s foreign policy strategy toward Beijing as well. The Hungarian government uses China as leverage with Brussels and to posture to Euroskeptic sentiment at home. Under Orbán, Hungary has positioned itself as a regional hub for China in Central and Eastern Europe, although the Chinese financial flows to the country have been far less than expected just a few short years ago. For Beijing, Hungary is a relatively open door in Europe, given the Orbán government’s embrace of China as a diplomatic and economic interlocutor and his search for partners in advancing his illiberal model of governance at home. For the Chinese leadership, he is a useful interlocutor to help deflect international criticism of and stymie European consensus on Chinese human rights violations, particularly in Hong Kong and Xinjiang.

State or government-friendly oligarchic control over the media stymies alternative views of Beijing, which enables leaders in both Budapest and Beijing to hail the relationship as a win-win. Positive media coverage helps compensate for the limited impact that Chinese soft power projection has had thus far in the country. Recent polling suggests that Hungary’s Western partners are viewed far more positively than China among average citizens—a finding that is in line with neighboring Poland and the Czech Republic.80 Hungarians harbor slightly negative views of China’s international clout and see Beijing primarily as a source of financing. China’s efforts to cultivate more positive views of itself among society at large—through public diplomacy such as Confucius Institutes or sister-city relationships—have largely fallen flat. Nonetheless, the positive top-down media coverage of China helps compensate for the limited impact of Beijing’s soft power efforts, particularly among Orbán’s key constituencies.

A BRIEF HISTORY

Budapest’s outreach to Beijing is not new. Like many former Warsaw Pact countries, Hungary formally recognized the People’s Republic of China in October 1949. Unlike other countries, however, both Hungary and China marked the seventieth anniversary of that diplomatic recognition with great fanfare in 2019.81 Relations ebbed and flowed during the Cold War depending on the ideological winds emanating from both capitals.82 Hungary was a pioneer of democratization in the Eastern bloc. The ruling Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party surrendered power in October 1989, a month before the Berlin Wall came down.

After the end of the Cold War, the trajectories of Hungary and China quickly diverged for about fifteen years. Eager to shed all remnants of the country’s communist past, Hungary focused on integrating with the West and had little interest in China. Orbán and his right-wing Fidesz party, which originated in opposition to the communist party, ironically criticized the Chinese Communist Party and its human rights record in the 1990s. During his first term as prime minister (1998–2002), Orbán met with the Dalai Lama, creating a spat between the two countries.83 Yet since returning to office in 2010, he has avoided antagonizing Beijing with similar engagements or criticizing China’s human rights record.84

The geopolitical and geoeconomic shifts of the past twenty years facilitated Orbán’s move closer to China. By the mid-2000s, around the time that Hungary joined the EU, Beijing began courting the countries of Southeastern, Central, and Eastern Europe. Chinese leaders saw new EU members as potential entry points into the union as a whole.85 These countries were close to lucrative markets farther west and increasingly integrated into pan-European logistics and supply chains.86 Yet it was far cheaper to do business in the region, where labor costs were lower and regulations less stringent. The lack of transparency in Orbán’s Hungary has since helped facilitate state capture, which is exacerbated by Hungary’s lax attitude toward investment screening and its willingness to skirt EU requirements on public tenders. Hungarian elites’ vulnerability to Chinese economic influence arises in large part from their eagerness to cooperate with Chinese investors for individual gain.87

However, it was Hungary’s socialist government, led by Péter Medgyessy, that first embraced Beijing in the mid-2000s, facilitating the first wave of Chinese economic investment in the country.88 Medgyessy today remains an advocate of engaging China. His long track record with Beijing dates back to his time as a minister in the pre-1989 communist government. He has continued to visit the country in his post-government career, frequently highlighting the country’s governance economic models in public speeches in China.89 His praise reflects consensus across the Hungarian political spectrum of China’s importance as a trade and investment partner.90 The bulk of early Chinese investment in Hungary during Medgyessy’s time consisted of small businesses in the trading and service sectors geared toward selling Chinese-produced goods.91 With time, however, multinational Chinese firms—including Bank of China, Huawei, Lenovo, Wanhua, and ZTE, among others—came to see the country as a stepping-stone for more ambitious endeavors across Europe.92

ORBÁN’S PIVOT

Orbán’s embrace of China is twofold. On the foreign policy front, it is part of his broader effort to enhance his leverage with the European Union. A country like China attaches few strings to its diplomatic and economic engagement when it comes to governance, human or labor rights, debt, or environmental issues—all areas where Orbán’s government has problematic track records. On the domestic front, engaging China is intended to gain economic assistance, which was seen by many Central and Eastern European countries as vital after the 2008 global financial crisis. Some Chinese investments, such as the controversial and costly plan to build a new rail line between Budapest and Belgrade, have been handed to Hungarian oligarchs with close ties to the government. The turn toward China helps Orbán play to Euroskeptic sentiments in Hungary, by showing his own citizens that the country has alternatives to the EU—which has helped the populist leader consolidate his hold over Hungarian politics. Orbán uses outreach to Israel, Turkey, and Russia for similar purposes.